THE MOMENTS OF A EXISTENCE

瞬視

The Moments Of A Existence

Introduction

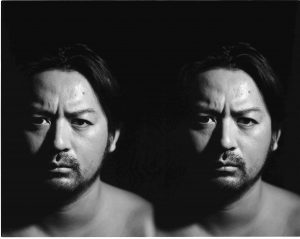

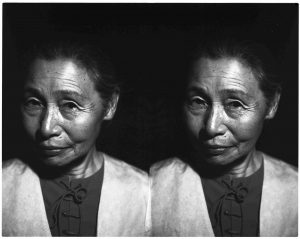

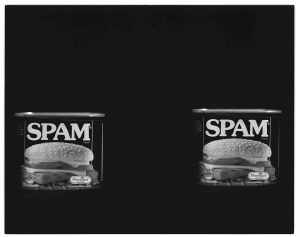

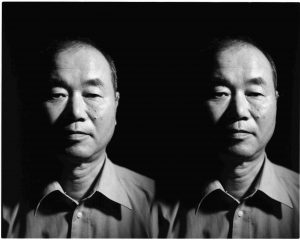

Do various “differences” to produce a subject in the both eyes of a top and the person and the diagram of the isosceles triangle to form show “a moment” to us?

瞬視

イントロダクション

そして、「僕」はいる。

「瞬間」の存在を哲学では証明出来ないそうだ。

時間の幅が無いものは「無」、そう意味が無いのだ。

よって「瞬間」が構成している「今」も無い。

瞬間と共に存在している僕らはいるのだろうか。

僕の存在を客観的に証明すべく考える。

桑嶋維

Michael Horsham(TOMATO)

The photographic image is a cypher for a moment, passed and captured. The cypher is the result, or evidence of codification of an act, or rather several acts. The cypher encodes the momentary action of releasing the shutter. Releasing the shutter: opening it at 1/24th, 1/100th of a second (or whatever length, on whatever film speed) will let light in on a focal plane and fix for near eternity the real and virtual objects inverted on the sensitised plate, pixel sensor field, emulsion or film. This used to be a special moment. This making of the image. Hold it. Flash! Bang! Wallop what a picture! Making a photograph was originally a one off, right up until the invention of the motor drive by Nikon in the 1970’s. But the act of making has been accelerating. In the century and a half of photographic reproduction perhaps the act has become banal, or at least so easy to iterate that it has ceased to become special. The more the means of “photographic” reproduction proliferates, the more we have access to the edited high lights of everyone with a smartphone. The cypher/image is now an instantly sharable codification of the moment. Arguably the democratisation of photography in this way is a good thing. It means that we are becoming (in the developed world at least) a more visually aware culture. On the other hand, the relentless adding to the compost of code, piling up in the server farms of the world as a result of the world’s image sharing obsession might also be evidence that everyone thinks they are image makers. But the deft use of Instagram’s filters or Flickr’s frames does not a photographer make. When you come across a photographer, out there in the world, making images, you sort of know it.

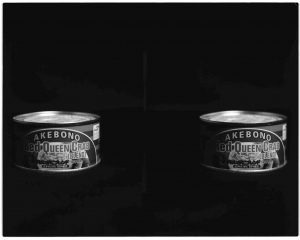

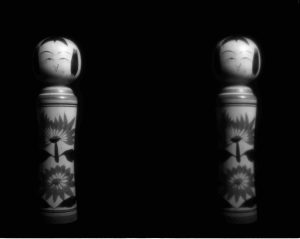

The image base, the approach of a photographer is distilled from a different impetus, a different set of desires. It’s not necessarily about creating the evidence of having seen a sunset, bought shoes or ordered the perfect brunch. No. Photographers who are actually photographers, tell stories through the images they make and tell them continuously. The codification of their acts of framing lighting and shutter release create a continuum of story telling, frame by frame, place by place, subject by subject. The eye of the photographer is key. If this little discourse works, it brings us neatly to the work of Tsunaki Kuwashima. The perfectly compelling images of the dogu – votive figures made in the the Jomon period which stretches back to 14,000 years BC – have within them a story element that might be impenetrable, mute and mysterious. These images raise questions in the mind in ways that most do not. This is portraiture of objects. Printing techniques and framing techniques aside, there is continuity in the approach and the atmosphere generated by these odd and essentially Japanese things. There is an obsession with Japanese things here. The series Togyu-tou Tokunoshima (The Island of Bullfighting, Tokunoshima) is also portraiture, but documentary portraiture. The fighting bulls of the little islands carry meaning and history in their scars, posture and musculature. They are representative of a culture that is historically, geographically and culturally Japanese – but beyond that they speak of a time when our human structures of communication and communion were simpler, more direct and arguably more powerful. The fascination with the symbology of human activity continues through the images of cock and dog fighting.

Repellent to some though these images, and the activities they represent, may be, the documentation of these activities reveal an anthropological fascination on Tsunaki’s part with just how we communicate with each other via means that are becoming increasingly rare. To see, capture document and tell those stories is the function of the photographer. To do it in a way that is visually compelling, arresting and at times beautifully is the role of the artist. Tsunaki Kuwashima successfully combines the two roles.

Michael Horsham is a Partner in the art and design collective Tomato. Tomato has been in existence for over twenty years and in that time as part of the studio Michael has published books, made installations, created commercials and campaigns for a wide range of clients from the BBC to the Okinawa Government, curated exhibitions and designed artworks and products and made music and digital media. Michael also teaches at the Royal College of Art and is always interested in the possibilities of new collaborations.

マイケル・ホーシャム

Michael Horsham(TOMATO)

アーティスト

写真とは、過ぎ去る一瞬をとらえるサイファーである。サイファーとは、一つの行為あるいはいくつかの行為を目に見える形にしたという結果、ないしは証拠である。サイファーとは、シャッターを切るという一瞬の行為を別の形に変換するものである。シャッターを切るということ、すなわちそれはシャッターを1/24秒、1/100秒(または長さやフィルムスピードがどのくらいであっても)開くことによって、焦平面に光を入れ、ときに本物だったり、ときにバーチャルだったりする被写体を感光板、イメージセンサー、乳剤やフィルムに転化し、半永久的に留めることである。かつてこれは特別な瞬間であった。画像を作るということ。構えて、フラッシュ!ボン! バシャ!見事な写真だ! ニコンが1970年代にモータードライブを開発して高速連写が可能になるまで、写真を作ることはもともと一度限りの事であった。しかし作る行為は加速し続けている。1世紀半の写真撮影の歴史の中で、おそらくその行為は平凡なものになってしまったように思う。少なくとも、あまりに簡単に何度も繰り返すことができるので、それは特別なものではなくなってしまった。「写真」撮影の手段が増殖することは、スマートフォンを持つ全員の選りすぐったハイライトの場面を見せられる機会が増えることを意味する。いまやサイファー/画像は、瞬間を手軽に共有できるコード、ないし成文化なのである。

議論の余地はあるかもしれないが、このような写真の大衆化というのは良いことだ。つまり我々は(少なくとも先進国では)視覚的な理解度の高い文化になってきているのだ。しかしその一方で、これでもかとコードという名の肥料が継ぎ足され、世界中のサーバーという名の畑に積み上げられている。この世界が画像共有に取りつかれた結果であり、誰もが皆イメージメーカーであると思っていることの証なのかもしれない。しかし、インスタグラムのフィルターやフリッカーのフレームを器用に使いこなすことで写真家になれるわけではない。写真家と聞いて思い浮かべるのは、世界のどこかに旅しイメージを作る人、そんなところではないだろうか。イメージの基礎となるもの、すなわち写真家のアプローチとは、普通と違う衝動や欲求などが抽出されて出来上がるものである。夕日を見たとか、靴を買ったとか、ブランチのオーダーが完璧だったとかの証拠として写真があるわけではない。否。自らのイメージを通して物語を伝え続けるのが本当の写真家であるはずだ。

フレーミング、ライティング、シャッターを切ると言った行為を目に見えるものにすることは、一コマ一コマ、その場所その場所、そのモノそのモノの連続した物語を作り上げることである。写真家の目こそが鍵である。このミニ講義を理解してもらえると、桑嶋維の作品の世界に近づくことができる。非常に人目を惹く土偶(始まりが紀元前14000年前まで遡る縄文時代に奉納された人形)の写真は、奥深く静寂で神秘的な物語を内に秘めている。これらの写真を見る時さまざまな問いが心に生まれてくる。それはほかの写真を見ている時には起こらないことである。これは物を肖像画のように撮影した写真である。印刷技術やフレーミング技術はさておき、この奇妙で極めて日本的な物が醸し出す雰囲気とアプローチには連続性がある。ここには日本のモノへの強いこだわりがある。闘牛島・徳之島のシリーズもまたポートレートであるが、こちらはドキュメンタリーポートレートである。この小さな島の闘牛たちは、その傷、体つき、筋肉で歴史を物語る。歴史的にも地理的にも文化的にも日本を代表するものではあるが、それ以上に人間のコミュニケーションやコミュニティがもっとシンプルで直接的で多分もっとパワフルだった時代を伝えてくれるものである。これら闘鶏や闘鶏の写真を通して人間の活動の象徴への興味が続いていくのである。

幾つかの写真やその写真が伝える活動は見るのが辛くなるようなものである。けれど、この活動のドキュメンタリー写真を通して、桑嶋 は我々が急速に珍しくなりつつある手段を使ってお互いどのようにコミュニケーションをとるものなのかという彼の人類学的な興味を表現しているのかもしれない。見て、事実を捉え、それを伝えることは写真家としての役目である。それを人を惹きつけられずにはいられないようなビジュアルで時には美しく見せるのはアーティストの役目である。そのふたつを両立しているのが桑嶋維なのだ。

マイケル・ホーシャム/Michael Horsham

イギリス生まれ。 アートデザイン集団 TOMATOのパートナー。TOMATOは1991年に設立以降イギリスにとどまらず国際的にもメジャーなクリエイティブ機関である。1994年から現在に至り、書籍デザイン、芸術インスタレーション及びコマーシャルやキャンペーンなど数多くの制作に関わってきた。クライアントはイギリス放送局(BBC)や沖縄県政府など。メデイア範囲も広く、アート、プロダクトデザイン、音楽やデジタルメデイア制作にも関わってきた。現在英ロイヤル・カレッジ・オブ・アートで講師を務めると同時に新たなコラボ企画にも興味を寄せる。