THE ETERNITY

久遠

The Eternity

Tsunaki Kuwashima

One day, I pondered, how did people without language or text communicate and express their thought ?

I wondered, is it only natural that an illiterate society suffered great difficulties intransmitting thoughts ?

But despite the trouble,the will was even stronger and residing within that will,regardless of time, nation or nationality,is the truth.

Japan until around the fifth century was an illiterate material culture society.

I dive deep into my consciousness to search the motives of our ancestors’ desires, letting the artifacts and their beauty guide me as they wish.

The message that survives death, decay and destruction: the truth is in the objects.

I believe that my mission is to photograph the truth, thereby immortalizing it with an eternal life.

Archaeological works I have photographed include stone burial chambers and tombs.

By capturing how our ancestors perceived the most feared fate of everyman(death)I begin not to conceptualize life but to experience it.

久遠

ある日、言葉を持たない時代の人々は何をどう伝えていたかという疑問が湧いた。

意思伝達はかなりの困難であったろうと容易く予想出来るからこそ、それでも伝えたかったことに、時代を問わない真実が宿っているのではと考えたからだ。

言葉を使わずに相手に伝えるということは、主に視覚もしくは聴覚伝達によるものになる。

視覚伝達の一種である写真に従事している僕は常に、制作において言葉を介さない交信による相互理解を心がけている。

日本では五世紀ぐらいまでの時代が文字不在の下での物質文化社会を形成していた。

僕は、遺物の醸し出す誘引性に魅せられるまま、先人たちにそれらを作らせる事となった動機を探るべく自身の意識の内へと潜入する。

死して、朽ちて、滅びてもなお伝えるべきものである真を写して久遠の生命を吹き込む。

今を生きる僕の使命だと信じている。

桑嶋維

Interview

Interviewer:Kazz Morohashi

To “UNEARTHED”

1)The reason why “a clay doll” was aimed at for the work?

Eternity

One day, I pondered: How did people without language or text communicate and express their thoughts? I wondered: it is only natural that an illiterate society suffered great difficulties in transmitting thoughts. But despite the trouble, the will was even stronger and residing within that will, regardless of time, nation or nationality, is the truth. Japan until around the 5th century was an illiterate material culture society. I dive deep into my consciousness to search the motives of our ancestors’ desires, letting the artifacts and their beauty guide me as they wish. The message that survives death, decay and destruction–the truth is in the objects. I believe that my mission is to photograph the truth, thereby immortalizing it with an eternal life. Archaeological works I have photographed include stone burial chambers and tombs. By capturing how our ancestors perceived the most feared fate of every man, ‘death’, I begin not to conceptualize ‘life’ but to experience it.

2) What is your reaction when you look at or handle dogu?

I felt like Taylor from the Planet of the Apes (1968) when I first set my eyes on a dogu. In the last scene, Taylor finds the destroyed Statue of Liberty and is damned that he has returned to his own civilization having traversed through time. My encounter with the dogu is indeed the same as Taylor’s discovery of the statue.

3) As an artist, what do you think about dogu (and specifically about each of the dogu that you photographed that we are including in the exhibition – see attached)?

Do you think about what they meant or how they were used in Jomon times? Do you think about what they mean to people today?

A letter without text

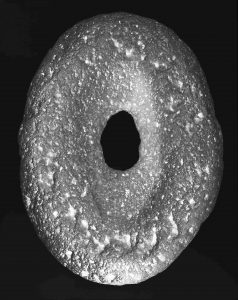

Dogu are mostly models of women. Dogu and some other ceramic items are not tools of daily life but are ritual implements, such as stone bars and swords. In the population declining late Jomon period when many of the dogu were made, the articulated motifs are said to represent fertility and childbirth. While ‘death’ is most feared, ‘birth’ is most welcomed. ‘Death’ is a return to the emptiness, while ‘birth’ is a creation by the ancestors to drive forward and build on knowledge discovered by earlier generations. Dogu teaches us that just as we were entrusted with our ancestors’ knowledge, it is our duty to create the next generation to pass on our intellectual beliefs. In an illiterate society, the Jomon people were not ‘transmitting’ explicit didacticism, but were giving us opportunities to think things through. A spirit desires a form. The spirit is implanted into the newly borne life, a life superimposed with knowledge that is loved and nurtured. Dogu are letters without text addressed to us in the 21st century.

4) Do the dogu present to you specific challenges when you make photographs of them?

Effortlessly having aged some 5000 years, my challenge is to create a new ‘dogu form’ injected with new life.

5) Do the dogu present to you specific possibilities when you make photographs of them?

My wish is to create photographs that offer new interpretation to dogu that challenge viewers to consider a truly new form and narratives of the dogu.

6) What ideas did you have in mind when your printed the dogu images as negatives?

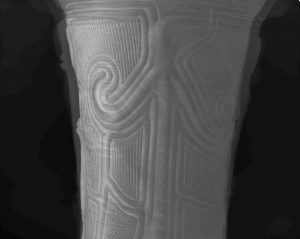

Usually on photographic prints, the incised patterns and lines created by the Jomon people appear as dark shadowed marks. I began to think that these lines are precisely the originality (identity) of the maker and similar to our fingerprints, individually unique. In order to feature these lines, I reverse negatives into positive images.

About “unearthed”

22nd June 2010 – 29th Aug 2010

This exhibition brings together prehistoric ceramic figurines from the Balkans and Japan for the first time. Over 100 figurines from Albania, Macedonia, Japan, Romania and the UK will be on display. These will include ornate Jomon figurines (known as dogu) from the Robert and Lisa Sainsbury Collection.

unearthed offers you the opportunity to get up close to these tiny, enigmatic figurines and to consider some of the mysteries of these ancient objects. Why were village dwellers in two unconnected regions making human forms from clay? Why were figurines commonly broken? What were they used for? What was their significance? How do they inform our understanding of early art? The exhibition poses these and other unresolved questions for art and archaeology.

unearthed challenges us to think more widely about figurines and the expression of the human form. This is explored with a series of contemporary artworks and images, including photographs and animations.

Collect your biscuit-fired figurine made by artist Sue Maufe from (with your ticket, subject to availability) and experience the tactile quality of the objects you will see in on display.

The exhibition is accompanied by a book, distributed by Oxbow Books, which is available from the Sainsbury Centre Gallery Shop.

unearthed is curated by Professor Douglass Bailey (San Francisco State University), Dr Andrew Cochrane (University of East Anglia) and Dr Simon Kaner (Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures).

For more information about the Sainsbury Institute, please visit their website

Click here »

UNEARTHED / インタヴュー

「土偶」を作品の対象とされた理由は?

久遠(くおん)

ある日、文字や言葉を持たない時代の人々は何をどう伝えていたかという疑問が湧いた。

他者との意思伝達はかなりの困難であったろうと容易く予想出来るからこそ、それでも伝えたかったことに、時代や国、人種を問わない真実が宿っているのではと考えたからだ。

日本では五世紀ぐらいまでの時代が文字不在の下での物質文化社会を形成していた。僕は、遺物の醸し出す誘引性に魅せられるまま、先人たちにそれらを作らせる事となった動機を探るべく自身の意識の内へと潜入する。死して、朽ちて、滅びてもなお伝えるべきものー真を遺物より知る。文明の歯車である僕の使命は真を写して久遠の生命を吹き込む事だと信じている。

考古学的な作品は他にもありますか?

他の考古学的な作品対象物としては、「石室」などの、所謂、「墓」を撮影している。人類共通の最も恐れることである「死」を僕たちの祖先がどう捉えてきたのかを知ることにより「生きる」ことを観念でなく実感するためでの作品である。

初めて土偶を見た時は?

初めて土偶を見た時の僕の反応は、映画「猿の惑星」(1968)の主人公テイラーになった気分だったのを覚えている。映画のラストシーンで、テイラーは崩壊した自由の女神を発見し、自分が時を越えて故郷である地球に帰って来ていたことを知り愕然とする。僕にとって土偶との出会いは、まさにテーラーにとっての自由の女神と同じだった。

アーティストとして、あなたにとっての「土偶」の意味とは?

無文字の手紙

縄文時代に作られた土偶のモデルはほぼ女性だ。土偶や一部の土器は、生活品や道具と違って、石棒や石剣と同様に祭祀道具である。人口が減少する縄文後期に多く作られたことや、そのモチーフからして、子孫繁栄、すなわち、子作りや安産を願ったものと云われている。人が最も恐れる事は「死」であり、最も喜ばしいことは「誕生」である。

「死」は無に還ることを意とするが、「誕生」は、先人が生み出し、作り上げた知の継続と発展を意とする全人類共通の認識だ。

僕たちが受け継いだ様に「次」の担い手を誕生させて育てる責務が僕たちにはあるということを土偶や土器は教えてくれる。

無文字社会の縄文時代においては、「伝える」ということは決して説明することでなく、考えさせると言う事なのだろう。魂は形を欲する。

次世代の生命に魂を入れて命とし、知識に心を入れて愛とし、育てていくのである。

土偶や土器は、縄文人たちから僕らへの文字の無い手紙だった。

あなたが作品を制作する時に、土偶が特別にもたらす影響とは?

すでに五千年の時を超えて現れた土偶だが、僕は新たなる「土偶像」を創り命を吹き込むように挑戦している。

「写真作品」制作の時は?

土偶を既存にない新たなる解釈が出来るような写真を創りだすことにより、それらを見た人々の中で真新しい土偶像が生まれ、語り継がれるように願っている。

土偶の写真作品をネガのようにプリントして制作したのはどうしてですか?

通常の撮影、プリントでは人(縄文人)が土偶を作り出す際に刻んだ箇所や線が黒く沈んでしまう。僕は、製作者(縄文人)が刻んだ一つ一つの線こそが、彼らが自身の作品に吹き込んだオリジナリティーの証であり、人それぞれが持つ指紋と同じではないかと考えた。

僕はそれらの線を暗闇から解き放つために、ネガティブをポジティブとした。

インタビュアー&日本語テキスト

諸橋和子

アーティスト。イギリス、アメリカで活動。日本の伝統工芸からデザインやキャラクター・アートに関心を持ち、主にグラフィック・デザイン、ナラティブ・デザイン、また教育デザインに関わっている。幼い頃から動物や自然界に興味を持ち、作品にも多くの動物キャラクターが紹介される。ロスのポップなエネルギーと色彩を愛し、日本の「ものづくり」文化に大きく影響される。

外部リンク

the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts (SCVA)

Unearthed展とは

会期:2010年6月22日から2010年8月29日

この展覧会は、先史時代に作られた、バルカン半島と日本の土偶が一堂に会する、初めての機会となります。日本、アルバニア、マケドニア、ルーマニア、そして英国から集められた100体を超える土偶が展示されます。展示品には、セインズベリーコレクションの所蔵品である、素晴らしい装飾を施された縄文時代の人型の置物(土偶)も含まれます。

Unearthed展は、皆さんがこれらの小さな謎めいた人形に親しみ、古代の遺物の謎に思いをはせる好機となるでしょう。

なぜ何の関連もない二つの全く別の地域に住む村人たちが、同じように土から人型の置物を作ったのでしょう?

その置物が破壊された状態で発見されることが多いのはなぜでしょう?

それらは何のために作られたのでしょう?

そしてどんな意味を持っていたのでしょう?

原始的な芸術に対する私たちの理解に、どんなヒントを与えてくれるのでしょう?

この展覧会は、そのような芸術や考古学上の未解決の謎について問題を提起します。

Unearthed展は、土偶や人間のカタチを表現するということについて、より幅広く考えるよう私たちをいざないます。

それは、本展覧会に展示された写真やアニメーションを含む、現代美術の作品と映像を通じて探求されます。

また、Sue Maufe氏(芸術家)から素焼きの置物を受け取って、ぜひ展示品の触感を体感してみてください。(入場券のご提示が必要となります。品切れの際はご容赦下さい)

この展覧会に付随して、オックスフォードブックスより、本が出版されます。この本はセインズベリーセンターのギャラリーショップでご購入いただけます。

本展覧会は、ダグラス・ベイリー教授(サンフランシスコ州立大学)、アンドリュー・コクラン博士(イーストアングリア大学)、シモン・ケイナー博士(セインズベリー日本芸術研究所)が監修しました。

セインズベリー研究所についての詳しい情報はホームページをご覧下さい。

The mission of the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures is to promote world class research and be a leader in the study of Japanese arts and cultures from the past to the present.

The Eternal Idols

Interviewed with Mami Mizutori, Executive Director of the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures,and Professor Nicole Coolidge Rousmaniere, Research Director at the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures.

Text by Mrs.Kazuko Morohashi

The Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures

Tsunaki Kuwashima has been chasing the ephemeral shadows of eternity. Does eternity exist? Is it tangible? Can the lens capture it?

Kuwashima’s work is highly acclaimed for its unconventional, mesmerizing and at times haunting style. For over a decade Kuwashima has pushed boundaries to visually define, in exquisite lyrical display, the opposing forces between mortality and eternity. He captures how we humans have tried to negotiate life and death throughout history and culture by casting our hopes on the existence of eternity.

Kuwashima explores the notion of ‘eternity’ through Japanese prehistoric clay figurines and pots from the Jômon period (14,000-300BC). By making references to these curious archaeological objects that often represent the human form, he attempts to show the link between the Neolithic society, who mediated their life circumstances by idolizing these objects in search of health and prosperity, and the contemporary Japanese. The Jômon people who had no script relied instead on making elaborate clay objects to communicate their worldviews. These objects, and in particular the enigmatic figurines or dogû, for example, were believed to have spiritual properties.

According to Professor Tatsuo Kobayashi, figurines acted as surrogates of those suffering from ailments and their clay body broken in the belief that the act will restore health. In fact, archaeological excavations produced most of the decorative figurines with what appear to be deliberate breakages of body parts. Kuwashima was perplexed by the damage as wasteful. But perhaps destroying such ornate objects is what makes us humans—to create something beautiful with the intent to harm it in order to solicit greater power than what man possesses, even if that wish is not granted, is what separates us from other species. In this light, Kuwashima sees the clay shards as fragment of the human heart, and that the will to pray for the wellbeing of loved ones is an eternal human emotion. Professor Nicole Coolidge Rousmaniere, Research Director at the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures, observes that his photographic style strives to seek the very essence of his subject matter: ‘his images are compelling as they suggest an unspoken narrative. He creates an emotive world without words’.

While Kuwashima captures these objects’ ‘eternal’ existence, he simultaneously reminds the viewers of the paradox of the eternal: the decay. Can ‘eternity’ really be eternal? His fascination with decay is articulated most clearly in the materials he chose to use. For instance his prints range from platinum palladium prints on paper that is out of production and can be regarded ‘extinct’, to collotype prints, known for their exceptional archival stability, and inkjet prints, the most widely available print type but with the shortest colorfastness. The image of ‘eternal’ depending on the medium it is printed on can dictate the life of eternity.

The ‘CUBE’ installation he presents investigates the way in which we try to encapsulate, protect and preserve ‘eternity’. By literally encasing images of ‘eternity’ in untreated steel framed boxes he calls the CUBE, Kuwashima challenges us to consider whether ‘eternity’ ought to be wrestled into a box for safekeeping. Given time, these steel cases will eventually rust and take on their own natural decaying process. He asks whether it is possible to conserve ‘eternity’.

The CUBE-headed manikins explore the narrative of how we embody ‘eternity’. These CUBEs contain double-sided images including one that is a mirror. On one side is an image of a prehistoric figurine, illustrating Japan’s ancient culture, or Japan’s ‘memory’, while the other is a mirror to reflect the viewer’s face. In Kuwashima’s mind our personal self-awareness is a manifestation of our own individual experiences and our ancient ‘eternal’ memories. Mami Mizutori, Executive Director of the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures, comments that ‘Kuwashima is an exceptional artist who explores our universal existential desires. His work speaks to us in a profound way that transcends geo-historical-cultural boundaries. We had the pleasure of working with Kuwashimain 2010 when an exhibition entitled unearthed curated by our Institute staff was shown at the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts in Norwich. His photographs of Jomon figurines exhibited at a gallery in the city centre complimented our exhibition in a way that captured the imagination and connected with many regardless of their age, gender, culture or history.’

Tsunaki Kuwashima is an award winning Japanese photographer.

He studied fine arts and photography at Central St Martin College and London College of Printing in 1994. He lived in London producing a body of photographic work before returning to Japan in 1998. He lives and works in Tokyo and Yamanashi Prefecture. Kuwashima has exhibited widely both nationally and internationally in both group and solo exhibitions, including the recent unearthed exhibition held at the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts and Foil Gallery vs. Zenkyoan contemporary art exhibition with Yoshitomo Nara and other prominent Japanese artists in Kyoto.

Nicole Coolidge Rousmaniere

Nicole Coolidge Rousmaniere is the founding Director and is currently the Research Director at the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Cultures, and Professor of Japanese Arts at the University of East Anglia, Norwich, UK. She was until recently the IFAC Handa Curator of Japanese Art at the Department of Asia, British Museum, and was the lead curator on the Citi Exhibition Manga held in the Sainsbury Exhibition Galleries, British Museum from 23 May to 26 August 2019. She received her PhD from Harvard University in 1998. In 2007 she was the lead curator for Crafting Beauty in Modern Japan at the British Museum. In 2010 she helped facilitate and translate the British Museum’s first manga, Hoshino Yukinobu’s Professor Munakata’s British Museum Adventure. In 2012 she wrote Vessels of Influence: China and the Birth of Porcelain in Medieval and Early Modern Japan (Bloomsbury Academic). Her recent translation of Tsuji Nobuo’s History of Art in Japan was published by Tokyo University Press and won the Japanese Translator’s award prize for 2018. In 2019 it has been reissued as a paperback from Columbia University Press.

Mami Mizutori

Mami Mizutori is a Japanese diplomat and international civil servant. After serving as Minister to the United Kingdom and Director of the Sainsbury Institute for the Study of Japanese Arts and Crafts at the University of East Anglia, she became the first Japanese woman to serve as Special Representative of the Secretary-General of the United Nations to the UN disaster management agencies.

永遠のアイドル

原文(英語)

ニコール・クーリッジ・ルーマニエール教授:セインズベリー日本藝術研究所リサーチディレクター、大英博物館学芸員

水鳥真美:セインズベリー日本藝術研究所総括役所長

諸橋和子:セインズベリー日本藝術研究所

桑嶋維(クワシマ ツナキ)は、儚い永遠の影を追っていました。

永遠は存在するのでしょうか?

それは実感出来るのでしょうか?

レンズは、それを捕えることが出来るのでしょうか?

桑嶋の作品は、その型破りな表現で人々を魅了し、同時に忘れられない衝撃があり、絶賛されています。

10年以上にわたって桑嶋は死と永遠の間での相反関係を視覚的に洗練された叙情詩調の表現においてより明瞭にしました。

永遠という存在に我々の望みを投げることによって、彼は歴史や文化を通して生死という命題の解決の糸口を作品化して我々に問いかけています。

桑嶋が「永遠」の概念を探るために撮影したものは、日本の有史以前の縄文時代(14,000-300BC)の土偶(粘土小立像)と器です。

多くの場合、人間の形を表現したと思われるこれら興味深い考古学オブジェクトー土偶や土器への考察を行うことによって、彼は健康と繁栄を求めて具象化された土偶や土器によって彼らの新石器時代の社会生活環境と現代日本社会とをつなぐ表現を試みています。

全く文字がなかった縄文時代の人々は彼らの世界観を伝えるために精巧な粘土オブジェクトを作っていました。土偶は、たとえば、治癒的な特性があると思われていました。

小林達夫教授によると、土偶は、病気や様々な行為によって苦しむ人々の代理として作られて、健康回復や祈願成就することで壊されました。実際には、考古学的な発掘調査では、装飾を施した土偶のほとんどは身体の部分を意図的に破損させていたことが分かっています。桑嶋は無駄なように思われる土偶の破壊行為に当惑していました。

しかし、おそらくそのような華やかなオブジェクトー土偶を破壊することは私たちを「人間」として形成する為に必要な要素の一つかもしれません。

人が備えている力よりもより強大な力を必要だと想像し、それを欲し、願うが為に、人が持ちうる能力を出し切って作ったものを敢えて破壊する行為ーたとえ願いがこもって無いとしてもーこの行為は人間と他の生物とを分けるある種の能力、行為です。

この観点から、桑嶋は、人間の心の断片として粘土ー土偶の破片を見て、そして愛する人の幸福を祈願する意志が永遠の人間に備わっている感情であると考えています。

ニコール・クーリッジ・ルーマニエール教授(セインズベリー研究所リサーチディレクター/大英博物館学芸員)は、桑嶋の写真のスタイルは彼の作品主題の本質を追求するために尽くしているとして、「桑嶋維の作品は縄文人らの暗黙の物語を示唆していて魅力的であり、彼は言葉を用いずに感情に訴えかける独自の世界を創り上げている。」と評しています。

桑嶋がこれらのオブジェクト「永遠」の存在を捉えている間、彼は同時に永遠と崩壊のパラドックスを見るものに連想させます。

「永遠」が本当に永遠になることができるんでしょうか?

彼が魅了されている永遠を阻害する現象である崩壊や腐敗に対する彼の考えは、彼が選んだ制作材料で最も明瞭に表現されています。

たとえば、コロタイプ・プリントやプラチナ・パラジウム・プリントやインクジェット・プリントがあり、それらを所謂デッドストックの印画紙や数多の種類から選び抜いた和紙や、最新プリントに対応して作られた新しい紙等にプリントや印刷する事によって、勿論、それら作品のアーカイブの安定性=命が変動し、それぞれの「永遠」を例示しています。

彼が創りだした「CUBE(キューブ)」は、作品をカプセル化して保護し、それは「永遠」を閉じ込めて保存しようとする手段の具象化であります。

「CUBE」と呼ぶ未処置の鋼のフレーム箱に入れることによって、やがてはこれらの鋼のケースはさびて、彼ら自身の自然な腐敗(=永遠の終焉)して行くプロセスが始まり、またその運命に逆らう行為(=延命)としてのメンテナンスを、生かせたいだけ続けていかねばならないという苦闘を強いることで桑嶋は作品所有者に「永遠」を実感させる事を要求しました。

彼は、「永遠」を保存することができるかどうか尋ねているのです。

CUBEの頭のマネキンは、我々がどのように『永遠』を体現するかという物語を示しています。これらのマネキンの頭部に据えたCUBEは、鏡であるものを含む両面イメージで構成されています。

見る者の顔を映す鏡面では、日本の古代の文化または日本の『記憶』を例示して、有史以前の小立像のイメージを表現しています。

桑嶋の考えにおいて、我々の個人の自己認識は、我々自身の個々の経験と我々の古代の「永遠の記憶」の現れなのです。

「桑嶋維は、我々のは我々の普遍的な実存主義の願望を探究する卓越した芸術家です。」と、水鳥真美( セインズベリー日本藝術研究所総括役所長)は、コメントしています。

そして、続けて、

「彼の仕事は、地理歴史上の文化的な境界を越える深い方法で、我々に話しかけます。

我々は桑嶋の作品を 2010年に セインズベリー日本藝術研究所 主催で開催された「UNEARTHED」展(英国ノリッジの the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts美術館) で展示することができました。ギャラリーに展示される縄文土偶の彼の写真は、年齢、性別、文化または歴史に関係なく、観る者に想像力を湧き立てて、多岐にわたる方面から桑嶋維の作品展示に敬意を頂きました。」と彼の作品を賞賛しています。

桑嶋維は、大木記念美術作家助成基金等を受賞した日本の芸術家です。

彼は、1994年に美術と写真撮影をセントラル・セントマーティン・カレッジとロンドン・カレッジ・オブ・プリンティングで研究しました。

1998年に日本に戻る前に芸術写真の主部であるロンドンに彼は住んでいました。

彼は日本では、東京と山梨県で活動しています。

グループと単独の展示(京都で奈良美智と他の著名な日本のアーティストとFoil Gallery主催の現代美術展(開催地:禅居庵/京都)や、現代美術展示のためにセインズベリー・センターで開催され、最近、公に展示された展覧会を含む)で、桑嶋維は全国的に、そして、国際的に、広く展示されて芸術家として認知されました。

ニコール・クーリッジ・ルーマニエール( Nicole Coolidge Rousmaniere)

ニコール・クーリッジ・ルーマニエールはセインズベリー日本藝術研究所の創設者、初代所長。現セインズベリー日本藝術研究所研究担当所長およびイースト・アングリア大学日本美術文化教授。最近まで大英博物館アジア部日本セクションにIFACハンダ日本美術キュレーターとして出向し、主任キュレーターとして、2019年5月23日から8月26日まで大英博物館のセインズベリー・エキシビション・ギャラリーにて開催された「マンガ展」に携わった。1998年にハーヴァード大学にて博士号を取得。2007年には大英博物館の「Crafting Beauty Exhibition 」を展示企画し、2010年には、大英博物館からは初のマンガ作品である、星野 之宣作「Professor Munakata’s British Museum Adventure(大英博物館の冒険)」の刊行に携わり、翻訳も担当。2012年には「Vessels of Influence: China and the Birth of Porcelain in Medieval and Early Modern Japan」(Bloomsbury Academic社)を書き著した。また、2018年には辻惟雄の「日本美術の歴史」を翻訳したものが東京大学出版会から刊行され、それが第55回日本翻訳文化賞を受賞した。2019年には同書のペーパーバック版がコロンビア大学出版より発売になった。

水鳥 真美

日本の外交官、国際公務員。駐英公使、イースト・アングリア大学付属セインズベリー日本藝術研究所所長等を経て、日本人女性初の国連事務総長特別代表として国連防災機関代表を務める。

諸橋和子/Kazz Morohashi

アメリカ育ちの日系アメリカ兼イギリス人。英ロンドン東洋アフリカ研究学院にて美術史修士 を取得後、英セインズベリー日本藝術研究所で数々の日本美術と文化の研究と国際的発信・促進に関するプロジェクトに関わる。現在は独自の制作活動やキュレーションも行い、企画は南アフリカから日本やイギリスをベースにした プロジェクトに関わっている。クリエイティブのネットワークづくりにも積極的で、国内外問わず今後も新たな出会いと交流に大きな期待を寄せる。

Michael Horsham(TOMATO)

The photographic image is a cypher for a moment, passed and captured. The cypher is the result, or evidence of codification of an act, or rather several acts. The cypher encodes the momentary action of releasing the shutter. Releasing the shutter: opening it at 1/24th, 1/100th of a second (or whatever length, on whatever film speed) will let light in on a focal plane and fix for near eternity the real and virtual objects inverted on the sensitised plate, pixel sensor field, emulsion or film. This used to be a special moment. This making of the image. Hold it. Flash! Bang! Wallop what a picture! Making a photograph was originally a one off, right up until the invention of the motor drive by Nikon in the 1970’s. But the act of making has been accelerating. In the century and a half of photographic reproduction perhaps the act has become banal, or at least so easy to iterate that it has ceased to become special. The more the means of “photographic” reproduction proliferates, the more we have access to the edited high lights of everyone with a smartphone. The cypher/image is now an instantly sharable codification of the moment. Arguably the democratisation of photography in this way is a good thing. It means that we are becoming (in the developed world at least) a more visually aware culture. On the other hand, the relentless adding to the compost of code, piling up in the server farms of the world as a result of the world’s image sharing obsession might also be evidence that everyone thinks they are image makers. But the deft use of Instagram’s filters or Flickr’s frames does not a photographer make. When you come across a photographer, out there in the world, making images, you sort of know it.

The image base, the approach of a photographer is distilled from a different impetus, a different set of desires. It’s not necessarily about creating the evidence of having seen a sunset, bought shoes or ordered the perfect brunch. No. Photographers who are actually photographers, tell stories through the images they make and tell them continuously. The codification of their acts of framing lighting and shutter release create a continuum of story telling, frame by frame, place by place, subject by subject. The eye of the photographer is key. If this little discourse works, it brings us neatly to the work of Tsunaki Kuwashima. The perfectly compelling images of the dogu – votive figures made in the the Jomon period which stretches back to 14,000 years BC – have within them a story element that might be impenetrable, mute and mysterious. These images raise questions in the mind in ways that most do not. This is portraiture of objects. Printing techniques and framing techniques aside, there is continuity in the approach and the atmosphere generated by these odd and essentially Japanese things. There is an obsession with Japanese things here. The series Togyu-tou Tokunoshima (The Island of Bullfighting, Tokunoshima) is also portraiture, but documentary portraiture. The fighting bulls of the little islands carry meaning and history in their scars, posture and musculature. They are representative of a culture that is historically, geographically and culturally Japanese – but beyond that they speak of a time when our human structures of communication and communion were simpler, more direct and arguably more powerful. The fascination with the symbology of human activity continues through the images of cock and dog fighting.

Repellent to some though these images, and the activities they represent, may be, the documentation of these activities reveal an anthropological fascination on Tsunaki’s part with just how we communicate with each other via means that are becoming increasingly rare. To see, capture document and tell those stories is the function of the photographer. To do it in a way that is visually compelling, arresting and at times beautifully is the role of the artist. Tsunaki Kuwashima successfully combines the two roles.

Michael Horsham is a Partner in the art and design collective Tomato. Tomato has been in existence for over twenty years and in that time as part of the studio Michael has published books, made installations, created commercials and campaigns for a wide range of clients from the BBC to the Okinawa Government, curated exhibitions and designed artworks and products and made music and digital media. Michael also teaches at the Royal College of Art and is always interested in the possibilities of new collaborations.

マイケル・ホーシャム

Michael Horsham(TOMATO)

アーティスト

写真とは、過ぎ去る一瞬をとらえるサイファーである。サイファーとは、一つの行為あるいはいくつかの行為を目に見える形にしたという結果、ないしは証拠である。サイファーとは、シャッターを切るという一瞬の行為を別の形に変換するものである。シャッターを切るということ、すなわちそれはシャッターを1/24秒、1/100秒(または長さやフィルムスピードがどのくらいであっても)開くことによって、焦平面に光を入れ、ときに本物だったり、ときにバーチャルだったりする被写体を感光板、イメージセンサー、乳剤やフィルムに転化し、半永久的に留めることである。かつてこれは特別な瞬間であった。画像を作るということ。構えて、フラッシュ!ボン! バシャ!見事な写真だ! ニコンが1970年代にモータードライブを開発して高速連写が可能になるまで、写真を作ることはもともと一度限りの事であった。しかし作る行為は加速し続けている。1世紀半の写真撮影の歴史の中で、おそらくその行為は平凡なものになってしまったように思う。少なくとも、あまりに簡単に何度も繰り返すことができるので、それは特別なものではなくなってしまった。「写真」撮影の手段が増殖することは、スマートフォンを持つ全員の選りすぐったハイライトの場面を見せられる機会が増えることを意味する。いまやサイファー/画像は、瞬間を手軽に共有できるコード、ないし成文化なのである。

議論の余地はあるかもしれないが、このような写真の大衆化というのは良いことだ。つまり我々は(少なくとも先進国では)視覚的な理解度の高い文化になってきているのだ。しかしその一方で、これでもかとコードという名の肥料が継ぎ足され、世界中のサーバーという名の畑に積み上げられている。この世界が画像共有に取りつかれた結果であり、誰もが皆イメージメーカーであると思っていることの証なのかもしれない。しかし、インスタグラムのフィルターやフリッカーのフレームを器用に使いこなすことで写真家になれるわけではない。写真家と聞いて思い浮かべるのは、世界のどこかに旅しイメージを作る人、そんなところではないだろうか。イメージの基礎となるもの、すなわち写真家のアプローチとは、普通と違う衝動や欲求などが抽出されて出来上がるものである。夕日を見たとか、靴を買ったとか、ブランチのオーダーが完璧だったとかの証拠として写真があるわけではない。否。自らのイメージを通して物語を伝え続けるのが本当の写真家であるはずだ。

フレーミング、ライティング、シャッターを切ると言った行為を目に見えるものにすることは、一コマ一コマ、その場所その場所、そのモノそのモノの連続した物語を作り上げることである。写真家の目こそが鍵である。このミニ講義を理解してもらえると、桑嶋維の作品の世界に近づくことができる。非常に人目を惹く土偶(始まりが紀元前14000年前まで遡る縄文時代に奉納された人形)の写真は、奥深く静寂で神秘的な物語を内に秘めている。これらの写真を見る時さまざまな問いが心に生まれてくる。それはほかの写真を見ている時には起こらないことである。これは物を肖像画のように撮影した写真である。印刷技術やフレーミング技術はさておき、この奇妙で極めて日本的な物が醸し出す雰囲気とアプローチには連続性がある。ここには日本のモノへの強いこだわりがある。闘牛島・徳之島のシリーズもまたポートレートであるが、こちらはドキュメンタリーポートレートである。この小さな島の闘牛たちは、その傷、体つき、筋肉で歴史を物語る。歴史的にも地理的にも文化的にも日本を代表するものではあるが、それ以上に人間のコミュニケーションやコミュニティがもっとシンプルで直接的で多分もっとパワフルだった時代を伝えてくれるものである。これら闘鶏や闘鶏の写真を通して人間の活動の象徴への興味が続いていくのである。

幾つかの写真やその写真が伝える活動は見るのが辛くなるようなものである。けれど、この活動のドキュメンタリー写真を通して、桑嶋 は我々が急速に珍しくなりつつある手段を使ってお互いどのようにコミュニケーションをとるものなのかという彼の人類学的な興味を表現しているのかもしれない。見て、事実を捉え、それを伝えることは写真家としての役目である。それを人を惹きつけられずにはいられないようなビジュアルで時には美しく見せるのはアーティストの役目である。そのふたつを両立しているのが桑嶋維なのだ。

マイケル・ホーシャム/Michael Horsham

イギリス生まれ。 アートデザイン集団 TOMATOのパートナー。TOMATOは1991年に設立以降イギリスにとどまらず国際的にもメジャーなクリエイティブ機関である。1994年から現在に至り、書籍デザイン、芸術インスタレーション及びコマーシャルやキャンペーンなど数多くの制作に関わってきた。クライアントはイギリス放送局(BBC)や沖縄県政府など。メデイア範囲も広く、アート、プロダクトデザイン、音楽やデジタルメデイア制作にも関わってきた。現在英ロイヤル・カレッジ・オブ・アートで講師を務めると同時に新たなコラボ企画にも興味を寄せる。